The Subliminal Sell: How Brands Influence Us Without Us Knowing

From whispered hoaxes to explosive legal battles, the history of subliminal messaging is a wild ride. This article cuts through the myths to reveal the science behind subconscious influence. We explore infamous controversies—from the Judas Priest trial to Disney's "hidden" secrets—and dive into how these scandals shaped modern advertising laws and ethical practices. Discover what actually works, what doesn’t, and how brands are still pushing the boundaries today.

BUSINESSMARKETING

Shrey Padhi

3/1/202515 min read

Hidden in plain sight

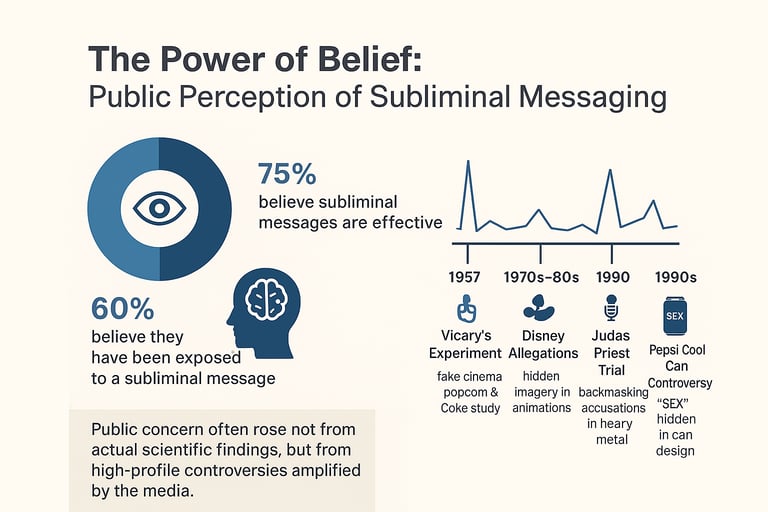

The notion of hidden persuasion has long fascinated and unsettled the public, particularly in the realm of advertising. Subliminal messages, defined as stimuli designed to influence perception and behavior below the threshold of conscious awareness, first sparked widespread debate with sensationalized claims in the mid-20th century. While early anecdotes of their effectiveness, such as rapidly flashed words in movie theaters, were later debunked, the core idea—that our subconscious can be swayed without our explicit knowledge—has continued to intrigue both marketers and consumers. This enduring fascination stems from a powerful, perhaps sometimes misinformed, belief in the mind's hidden vulnerabilities to subtle cues.

In modern advertising, the application of subliminal techniques has evolved far beyond fleeting flashes or whispered phrases, incorporating sophisticated psychological principles and empirical research. From the strategic use of color theory and symbolic imagery in logos to the subtle emotional appeals embedded within narratives and audio, advertisers subtly prime consumer responses. However, the use of such covert methods raises significant ethical questions regarding transparency, informed consent, and potential manipulation. This article will delve into the empirical research underpinning subliminal messaging, explore its controversial history in various media, illustrate how these insights inform contemporary advertising strategies, and finally, address the crucial ethical considerations for responsible deployment of these powerful techniques.

The history

Subliminal messages, or subliminal priming, is not at all a recent topic of discussion. The roots of the discussion on subliminal messages can be traced all the way back to the mid-1900s when psychologist James Vicary faked a report on subliminal priming in one of his published studies. This started the misconception about the mechanics of imparting subliminal messages. He had claimed that by flashing pictures of Coke and popcorn before movies started at the cinema, he was able to raise the sales of both. When he was unable to replicate these results in future experiments, he confessed to manipulating the data for publicity.

While Vicary's stunt brought attention to the topic, it also established a huge misconception that fuels many urban legends to this day. A 1979 Time magazine report, for example, claimed that departmental stores were reducing shoplifting by embedding subaudio messages in their in-store music. One East Coast chain even reported saving a whopping $600,000 over a nine-month period, seemingly proving the effectiveness of this technique.

However, in 1985, two psychologists, Vokey and Read, published their findings on "backmasking"—the method of embedding messages in audio tracks that are audible only when played backward. Their study suggested that subliminal messages are nothing but coincidental cues and that chance plays a vital role in their perceived effect on the listener. At the time, there was a lot of speculation that backmasking was being used by many bands, including The Beatles, The Eagles, and Judas Priest (the latter was accused of using backmasking, which resulted in two teenagers committing suicide and leading to court trials). While some of these famous bands did admit to using backmasking, they clarified that the technique was used mainly for aesthetics—to add a different layer to the sound track.

This notion of admittance from influential figureheads in the music industry inadvertently drew attention to the blockbuster study by Vokey and Reed, which tested if backmasking actually works as a subliminal cue. They recorded messages backward and asked a set of people (subjects) to listen to them continually and later to pick out any meaning in them. None of the subjects were able to pick out any meaning in what they heard. On further investigation, no major behavioral changes were recorded, nor was anything unusual noticed. They, therefore, in 1985, concluded in their study that backmasking of any kind is completely ineffective to a person’s mind. The research published by Vokey and Reed was a comprehensive one. It covered not just backmasking but also other subliminal stimuli, like subvisual, and labeled them as an ineffective method to influence a person’s thinking.

But unconvinced proponents, fuelled by their nature of academic stubbornness, continued the debate of subliminal priming. Branding subliminal messages akin to the intimate nature of a whisper, contemporaries of Vokey and Reed were coaxed that they work. It was only a matter of fact to figure out how.

In 1999, psychologists Adrian North, Jennifer McKendrick, and David Hargreaves conducted an experiment in a wine shop. Over a two-week period, they played stereotypical German and French music on alternate days and later noted the sales of the corresponding German and French wines. On the days when German music was played, the sales of German wines were significantly higher than usual. On alternate days when French music was played at the shop, the sales of French wines were higher than usual. The customers of the shop were asked to fill out a questionnaire, on which they clearly stated that they did not recall any particular type of music being played at the store and that they just “felt” they wanted to try the German or French wines on that particular day. The outcome of this study underscored the ongoing frustration of academics around the world to answer the question regarding the effectiveness of using subliminal messages in media.

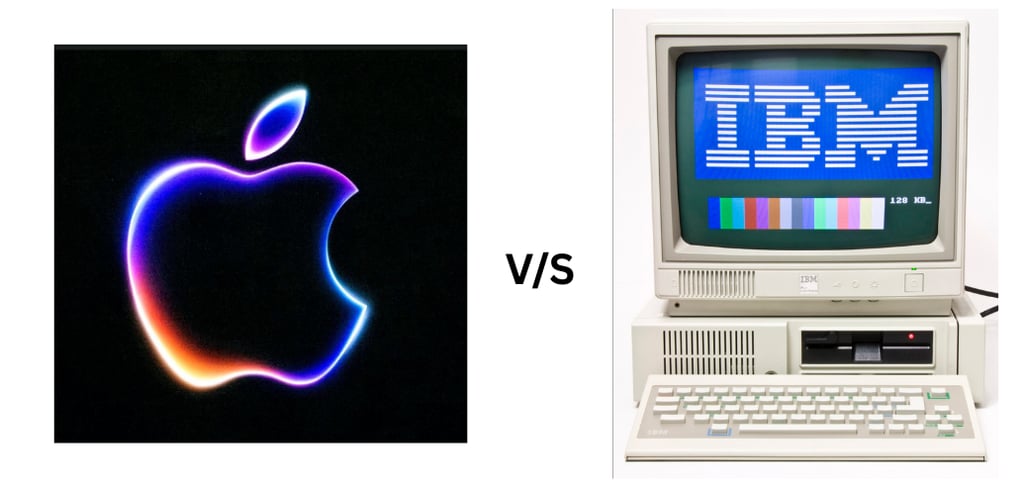

Fitzsimons, another psychologist, conducted an experiment in 2001 to test the effects of subvisual stimuli. He had called top achievers of a college batch for a social creative test. In this test, the college students were first segregated into two groups and then were asked to mention as many unusual uses of a brick as possible. However, before doing so, one of the two groups of students was flashed with an Apple logo (the company), and the other group of students with the IBM logo (the students were not informed of this happening).

This group of students that was flashed with the Apple logo could list significantly more unusual uses of a brick than the group of students that was flashed with the IBM logo. Fitzsimons concluded that this happened due to the structure of the brain and its methods of storing information. When the students were flashed with the Apple logo, a company known for its innovation in products like the iPod, iPad, and iPhone, it activated nodes often associated with creativity. As a result, they were able to come up with a wider variety of ideas for using a brick compared to the students who were flashed with the IBM logo—a company that had been seen as less innovative for quite some time.

The experiment conducted by Karremans, Stroebe, and Claus in 2006 guided the world to a final conclusion. The scientist trio conducted an experiment with the famous soft drink Lipton Ice Tea. They began with an initial questionnaire for the participants, who were then segregated into two groups. One group was subliminally primed with the message to choose between Lipton Ice Tea and another beverage (Spa Rood). The participants were then asked to choose between the two beverages. The results were not consistent with the urban legend; however, the trio went a step further and assessed the participants’ intentions of choosing Lipton Ice Tea over the other beverage. The participants who were reportedly thirsty and subliminally flashed with the picture of Lipton Ice Tea were more likely to choose it.

The academicians concluded that since participants' thirst increased the likelihood of making a subliminally primed decision, a pre-existing thought is a prerequisite for successful priming. However, this widely accepted conclusion was the product of not just comprehensive experimentation and research conducted by academics; lawmakers, journalists, parents, and other contemporaries also took part in refining this understanding of how subliminal priming works.

The controversies

The drama surrounding the phenomenon of subliminal messages had fuelled many fantastic rumours. I vividly remember, during my middle school days, in the late 2000s, I was learning how to play Hotel California by Eagles on the guitar when a senior of mine had interrupted my focused practice and mentioned “If you manage to play all the notes, in time, and backwards, you will summon the demon because Eagles has masked demonic ritual spells, which as a result get activated upon playing backwards”. Naturally in between practice, I didn’t have the capacity to think beyond what was told by my senior. But once my practice was done, I approached my music teacher, who confirmed the existence of subliminal cues in songs, but to my disappointment dismissed the myth of demonic prowess of the cues. Such was the extent of mystery that surrounded a seemingly simple technique which was allegedly used widely.

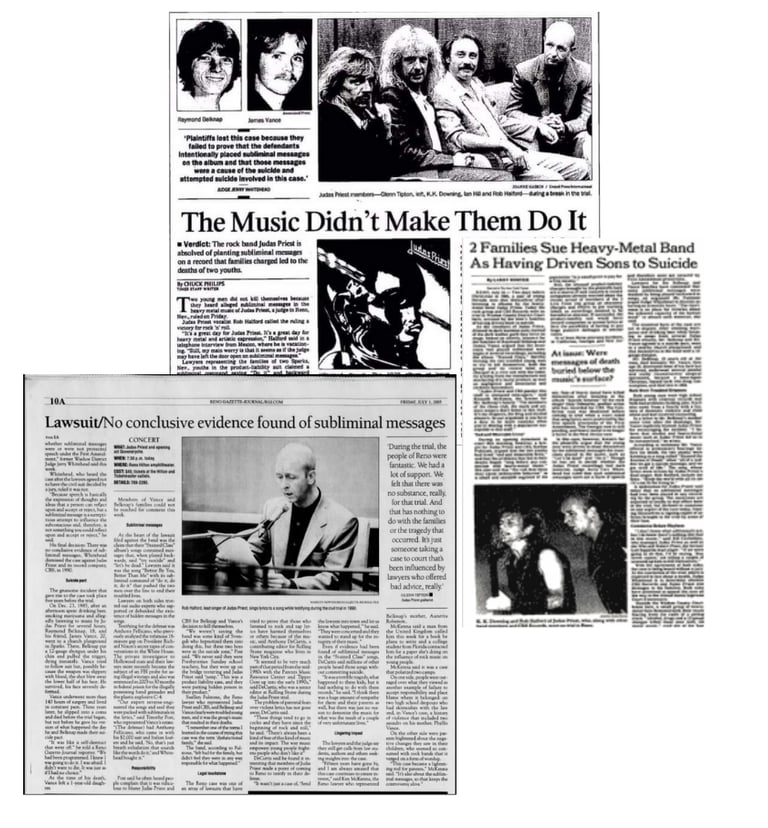

Perhaps the most notable controversy is of the recent inductee of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, English heavy metal band, Judas Priest. It was one of the most high-profile incidents involving allegations of subliminal influence in music. The case brought significant attention to the ethical and psychological implications of backmasking and sparked widespread debate about whether subliminal messages could drive harmful behavior, such as suicide.

The 1990 Judas Priest trial centered on a devastating tragedy: two young men, James Vance and Ray Belknap, entered a suicide pact after listening to the band's album, "Stained Class." Their families filed a lawsuit, alleging that a subliminal message of "do it" was hidden in the song "Better by You, Better Than Me" and had incited the suicide attempts. While the case became a flashpoint for a broader moral panic about heavy metal music, the judge ultimately ruled in favor of Judas Priest, concluding that even if such messages existed, they could not be proven to have caused the boys' actions.The trial highlighted the deep-seated public fear and uncertainty about the power of hidden influences, even as legal and scientific experts questioned the very effectiveness of subliminal persuasion.

During the Judas Priest subliminal message trial, lead singer Rob Halford admitted to recording the words "In the dead of the night, love bites" backwards into the track “Love Bites”, from the 1984 album Defenders of the Faith, however, Halford claimed that "When you're composing songs, you're always looking for new ideas, new sounds."

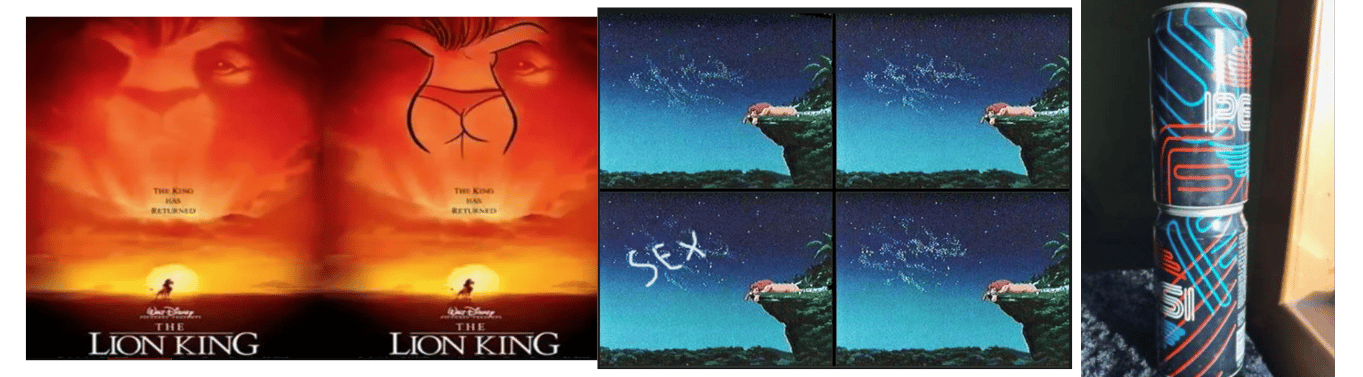

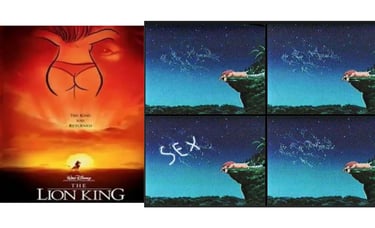

Disney’s animated films, such as The Lion King and Aladdin, which were scrutinized for allegedly embedding suggestive imagery and phrases that sparked outrage among parents.

Disney's "The Lion King" also became the subject of a major controversy, with claims that the word "SEX" was subliminally embedded in the film. The most famous instance is a scene where Simba flops down on a cliff, kicking up a cloud of dust that critics claimed formed the letters "S-E-X." While some have argued the word was a deliberate Easter egg, a former animator stated it was an intentional nod to the film's Special Effects team, spelling "SFX." The accusation was further amplified by an anti-abortion group that was already boycotting Disney at the time. Despite Disney's repeated denials and subsequent alterations to the scene in later releases, the rumor persists as one of the most well-known examples of alleged subliminal messaging in popular culture.

The widespread circulation of a faked poster for The Lion King is a powerful example of how public anxiety over subliminal messaging had reached a fever pitch. The fabricated image, which supposedly showed a naked woman superimposed on Simba’s nose, was a hoax, but it was accepted as truth by many parents already wary of hidden content. This incident wasn't about a real message, but about the public’s readiness to believe in one. It serves as a clear indicator of how fragile trust in media had become. The controversy demonstrates that by the 1990s, the topic had become so delicate that people were actively looking for hidden signs, making them cynical and critical of almost any media they consumed. This environment of suspicion transformed a simple animated movie into a cultural battleground, showing that the power of a rumored subliminal message could be far greater than that of a real one.

The controversy over the Pepsi "Cool Cans" in the 1990s highlights the power of urban legends in modern media. The limited-edition cans, featuring abstract neon designs, sparked a widespread rumor that the patterns formed the word "SEX" when stacked. This claim, though dismissed by Pepsi as a case of pareidolia, fueled a moral panic similar to the controversies surrounding Disney and Judas Priest. While many sources claim the cans were recalled due to public outcry, this is a misconception; they were simply removed from shelves at the end of their scheduled summer promotion. The false narrative of a recall demonstrates how public anxiety about subliminal messages can transform a simple marketing campaign into a cultural flashpoint, proving that a compelling rumor can often be more powerful than the truth.

These controversies highlight a history of hiccups in subliminal messaging, often exaggerating its power but exposing the real risks of bypassing conscious consent. Today, these missteps have prompted a shift toward more transparent and ethical practices. Brands have moved away from overt subliminal tactics toward subtler, psychology-driven strategies like emotional storytelling. Ethical considerations, inspired by cases like Judas Priest and Disney, now prioritize consumer autonomy, clear disclosure, and avoiding harm, particularly to vulnerable audiences like children, ensuring these techniques align with responsible advertising standards.

Ethical dilemma & regulations

So, do subliminal messages hold the power of mind control? The short answer is no. But that 'no' comes with a massive asterisk.

The sinister aura of subliminal messages doesn't live up to the urban legends of the 20th century. It is now widely accepted that subliminal messages do work, but only to reinforce pre-existing needs or goals. They are not universally persuasive but rather reinforce pre-existing needs or goals. This understanding was solidified by subsequent empirical studies and intense public discourse that sought to move beyond the sensationalized, fantastical ideas often associated with subliminal influence.

The widespread public outcry and political pressure that arose from the subliminal messaging controversies of the mid-to-late 20th century directly prompted a legal and regulatory response. Rather than waiting for irrefutable scientific evidence of harm, lawmakers and governing bodies took preemptive action based on the principle that the deceptive nature of subliminal advertising was itself a violation of public trust.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) led the charge in the United States. In a landmark 1974 policy statement, the FCC declared that the use of subliminal techniques in broadcasting was "contrary to the public interest" and a form of deception. This ruling didn't ban subliminal advertising based on its proven effectiveness, but rather on its deceptive intent. The FCC's position was that even the attempt to bypass a viewer's conscious mind for commercial gain constituted a violation of a broadcaster's license obligations. This legal stance, which focuses on the principle of consumer autonomy, has been a cornerstone of broadcast regulation ever since. Similarly, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) can address such practices under its broader authority to prohibit "unfair or deceptive acts or practices" in commerce.

These regulations were tested during the 2000 U.S. presidential election with the infamous "RATS" ad. The George W. Bush campaign released an ad criticizing Al Gore's health plan, which briefly flashed the word "RATS" over a segment on the plan's cost.

While the duration of the flash was likely not subvisual to all, the perceived deceptive intent behind it led to a formal complaint to the FCC. Though no final sanction was issued, the public backlash was immediate and severe, forcing the Bush campaign to pull the ad. This incident did not prove the effectiveness of the message, but it definitively demonstrated that the public, empowered by decades of regulatory and media discourse, would not tolerate perceived attempts at subliminal manipulation. The controversy underscored that laws, even if not strictly enforced with a heavy hand, serve a powerful role as a deterrent and a public standard of ethics for advertisers.

In the United Kingdom, the primary regulatory body is the Office of Communications (Ofcom). Established in 2003, Ofcom is a "super-regulator" that consolidated the functions of five different agencies, giving it broad authority over television, radio, telecommunications, and postal services. Ofcom's core mission is to protect the interests of citizens and consumers by promoting competition and safeguarding the public from harmful or offensive content. Its Broadcasting Code is a key document that all licensed broadcasters must follow. While the code does not explicitly mention "subliminal messages" as a stand-alone term, it has a clear stance against broadcasting material that could "exploit" the audience or "cause harm." Ofcom has investigated and sanctioned broadcasters for using suggestive or misleading content, which falls under the umbrella of subliminal techniques. The UK's approach, similar to the FCC, is to prohibit deceptive practices that bypass a consumer's conscious consent.

While the UK has had a long-standing ban on subliminal advertising since 1958, one notable incident involved the satirical news program Brass Eye in 1997.

In an episode of the show, a single frame was intentionally inserted containing derogatory language about the then-head of Channel 4, the network that aired the program. This was not a commercial advertisement, but it was a clear and deliberate use of a subvisual image. The content, being a personal attack rather than a commercial message, distinguished it from the typical "buy this product" variety of subliminal messages. While the channel itself investigated and confirmed the message was deliberate, the case did not result in a major legal battle because the use was for comedic and satirical purposes. The fact that the regulator's predecessor, the Independent Television Commission (ITC), was involved in this investigation and subsequent discussions, showcases a similar regulatory posture to the FCC's: a zero-tolerance policy towards any intentional attempt to convey messages below the threshold of conscious awareness, regardless of their commercial or political nature.

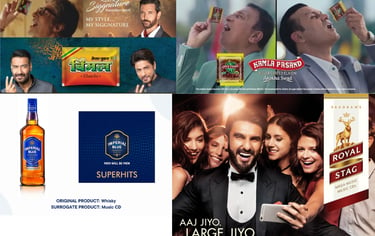

While countries like the U.S. and the U.K. have historically focused on subliminal messaging, a broader ethical challenge exists in many nations, including India. Here, the discourse isn't dominated by hidden messages but by a different kind of regulatory bypass: surrogate advertising. In India, the Advertising Standards Council of India (ASCI) and the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) have strict rules prohibiting the direct promotion of harmful substances like tobacco and alcoholic beverages. However, advertisers have found a way around these regulations by creating campaigns for non-banned products from the same brand. For instance, a brand known for its whisky might advertise a brand of soda or music CDs with a very similar name, logo, and visual aesthetic. This strategy is not about hiding a message but about creating a strong, subconscious link between a legal product and a forbidden one.

This practice, known as surrogate advertising, has been a source of ongoing controversy. For example, a popular alcohol brand may run a high-budget ad campaign for its bottled water or soda, featuring the same actors and jingle as its old alcohol ads. The message is clear to the public: the ad is promoting the alcohol, not the unrelated product. The ethical dilemma here is profound. It's a method that operates in a gray area of the law, technically adhering to the letter of the rules but brazenly violating their spirit. Unlike the subliminal messaging of the past, which was often a rumor, surrogate advertising is a widely recognized strategy. It demonstrates how advertisers can exploit loopholes to reinforce a brand image and product associations in the public mind without explicit messaging.

This is evidence that even in the absence of hidden, sub-visual messages, advertisers will push the boundaries of regulatory frameworks. This requires a shift in focus from simply banning "subliminal" content to a broader ethical consideration of advertising intent and consumer manipulation. The ASCI, while a self-regulatory body, has often called out such practices and issued warnings, but the issue persists, proving that the ethical debate is less about the technical definition of "subliminal" and more about the fundamental principles of transparency, consumer autonomy, and truth in advertising.

Closing notes

Over the last century, the public perception of subliminal messaging has evolved from a feared form of mind control to a nuanced understanding of its actual, limited effects. Extensive academic research now confirms that while subliminal messages do work, their effectiveness is highly conditional. They cannot plant a new idea or desire in a consumer's mind; instead, they can only reinforce a pre-existing thought or need. For instance, a subliminal message for a beverage will only prompt a consumer to buy it if they are already thirsty. This revelation was not solely the product of scientific study but also a result of intense public scrutiny and sensationalized media events.

The public's cynicism was fueled by hoaxes like James Vicary’s fabricated study and controversies where subliminal messages were rumored to have caused tragic events or been hidden in family-friendly media. These incidents, though often debunked, damaged the reputations of major corporations and galvanized public pressure for regulation. In response, governments established bodies like the FCC in the U.S. and Ofcom in the UK, which banned deceptive subliminal broadcasting, not necessarily because the messages were effective, but because the very act of attempting to manipulate a person's subconscious was deemed unethical and against the public interest.

This has led to a modern environment where overt subliminal tactics are largely avoided, not just due to legal restrictions but because of the potential for severe brand damage and a loss of consumer trust. However, the core principle of subliminal influence persists in more subtle and ethical ways, such as the use of color psychology or emotional branding. In some countries like India, this principle is even stretched into the gray area of surrogate advertising, where brands indirectly promote banned products like tobacco and alcohol by marketing a legal product under the same brand name. Ultimately, the history of subliminal messages highlights a crucial point: the ethical debate in advertising has shifted from a discussion of mind control to a focus on consumer autonomy, underscoring the delicate balance between influencing a consumer and respecting their right to make informed choices.

Further reading & references

Academic Articles

Vokey, John R., and J. Don Read. "'Subliminal Messages': Between the Devil and the Media." American Psychologist, vol. 40, no. 11, 1985, pp. 1231–39.

North, Adrian C., et al. "The Influence of In-Store Music on Wine Selections." Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 84, no. 2, 1999, pp. 271–76.

Fitzsimons, Gavan J., et al. "Automatic Effects of Brand Exposure on Motivated Behavior: How Apple Makes You Creative." Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 35, no. 1, 2008, pp. 21–35.

Karremans, Johan C., et al. "Beyond Vicary's Fantasies: The Impact of Subliminal Priming and Brand Choice." Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 42, no. 6, 2006, pp. 792–98.

Journalistic and Legal Sources

"The Power of Positive Flashing." Time, 10 Sept. 1979.

"Judas Priest: The Lawsuit Over Better By You, Better Than Me That Shook The Metal World." YouTube, uploaded by Rock and Roll True Stories, 24 June 2022. The video discusses the lawsuit and provides a concise overview of the events.

Disney's The Lion King and the "SEX" Controversy: Mikkelson, David. "Lion King Subliminal." Snopes, 29 May 1995, www.snopes.com/fact-check/lion-king-subliminal/.

Pepsi's "Cool Cans" Controversy: Mikkelson, David. "Pepsi 'Sex' Subliminal Ad." Snopes, 28 May 1995, www.snopes.com/fact-check/pepsi-sex-subliminal-ad/.

The "RATS" Political Ad: A detailed account is available through multiple news archives. An excellent source is the Center for Media and Democracy, which documented the event at the time.

Regulatory Bodies & Ethical Discussions

FCC Regulations: Federal Communications Commission. "FCC Policy Statement on Subliminal Advertising." Public Notice, 1974.

Ofcom (UK): Office of Communications. "The Broadcasting Code." Ofcom, 2018.

ASCI (India): Advertising Standards Council of India. "Code for Self-Regulation in Advertising." ASCI.