Homo Ludens - A Path to Evolution

Play isn’t a hobby—it’s evolutionary infrastructure. Drawing from Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens, this essay explains why humans build “magic circles”: voluntary worlds of rules that let us safely touch infinity without being consumed by it. From chess to modern game loops, and from classrooms in Dead Poets Society and Taare Zameen Par to courtrooms and diplomacy, we trace how constraint creates meaning—and what breaks when the circle collapses.

CULTUREPSYCHOLOGY

12/27/2025

The set up

The theory of evolution, so widely accepted and rigorously researched, has answered countless questions objectively. It explains why high-yield seeds transformed agricultural yield, why our anatomies are built as they are, why vestigial organs like the appendix remain. But evolution's mechanisms, while thoroughly documented, don't quite answer certain behavioral questions we observe in human development.

Evolution explains why some populations tolerate certain strains of common cold better than others. But it struggles to explain why children—across cultures, centuries, and contexts—instinctively create pretend worlds. Ghar-ghar in India, playing house in America, role-playing games across every society: children don't learn these from instruction manuals. They design them by picking up on traits they want to mimic, systems they want to inhabit, rules they want to test. The impulse is genetic, embedded in neural architecture inherited from ancestors who learned survival through play-fighting, through ritualized performance, through bounded simulation before the stakes became real.

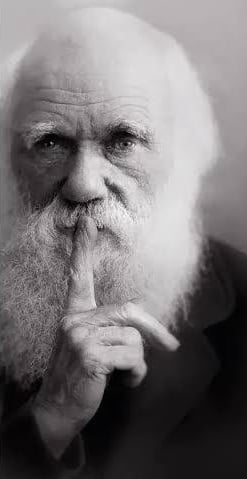

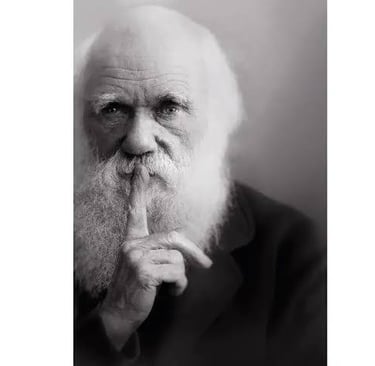

This is where Johan Huizinga enters. In his 1938 masterwork Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture, Huizinga proposed something unsettling: play is not the frosting on civilization; it is the essential mechanism through which humans navigate complexity, learn survival, and ultimately build culture itself. Play is not ornamental. It is foundational. And if we accept this, then the question shifts: if play is hardwired into our genes, if it is how creatures learn to survive, then perhaps the design of games—the structure of play itself—mirrors something fundamental about how human consciousness evolves.

The definition: Homo Ludens

Chess, a game with 64 squares, six-piece types, and rules simple enough to teach a child perfectly exemplifies Huizinga’s insights. Claude Shannon calculated that a 40-move chess game contains approximately 1,012,010,120 possible variations—more configurations than atoms in the observable universe. However, we do not play chess to solve it; that would exceed any human lifetime. We play to touch infinity in controlled doses, returning to ordinary reality shaped but not consumed by what we have encountered.

This is the paradox Huizinga identified: games are structured confrontations with infinity, offering us experiences of boundlessness we can survive, contained within rules we freely choose to obey. Huizinga outlined four pillars that define all authentic play, the architecture that makes this containment possible:

The First Pillar is Voluntary Entry. Play must be freely entered and freely abandoned. No coercion, no obligation beyond what we impose on ourselves. This autonomy grounds the experience in choice, making infinite complexity safe—we know we can leave, which paradoxically allows us to venture deeper.

The Second Pillar is Rule-Bound Structure. Rules are not chains but pathways through chaos. Without rules, infinite options paralyze us. The 50-move rule in chess prevents literally infinite games. A clearly defined ruleset creates channels through which we navigate with purpose. Rules transform the boundless into the navigable.

The Third Pillar is Separate Space and Time—the Magic Circle. A "temporary world within the ordinary world" where different laws apply. Inside this bounded realm, consequences become symbolic rather than material. Death is not final; failure is educational. The ordinary world's norms hold no dominion here.

The Fourth Pillar is Meaning-Laden Achievement. Play's outcomes carry significance beyond the immediate action. A victory, a completed structure, a discovered secret—these transform infinite effort into singular, memorable events. Achievement anchors player experience and validates time spent exploring the boundless.

Together, these four pillars form an architecture capable of containing infinity, allowing human beings to engage with overwhelming possibility without being consumed by it. They are not restrictions but liberations—they make boundlessness bearable.

The Game frame

Games across every era inculcate Huizinga's pillars. In chess, the magic circle is the 64-square board, the voluntary entry is choosing to sit down, the rules are the piece movements and the 50-move limit, and meaning emerges when victory transforms into mastery over numerical infinity—the recognition that 1,012,010,120 variations exist yet you can navigate them through pattern recognition.

But what happens when the boundary ruptures? Paul Morphy, the American chess prodigy of the 1850s, defeated every challenger from America to Europe. Playing eight opponents simultaneously while blindfolded, he had crossed into infinity itself—he was no longer playing a game but channeling something beyond ordinary human engagement. Yet after achieving total dominance, Morphy abruptly retired. What followed was decades of mental unraveling: paranoia, delusion, social isolation. He died at 47, penniless and forgotten, convinced that invisible conspirators plotted against him. One theory suggests his genius had opened a hidden door that his psyche could not sustain. Having glimpsed chess's bottomless depth, he could not return to ordinary concerns. The magic circle had collapsed. The infinite was no longer something to play with; it had become obsession consuming him.

This tragedy reveals the paradox: within the four pillars, infinity is wondrous; outside them, it becomes catastrophic.

A competent chess player survives numerical infinity through bounded rationality—using pattern recognition to approximate rather than calculate every variation. When Morphy stopped sampling and tried to drink directly from the well—when voluntary engagement transformed into compulsion—the infinite devoured him.

Modern games instantiate these pillars more deliberately. Hades II, a roguelike where every run ends in death yet advances story and understanding, respects voluntary engagement (difficulty modifiers you control), rule-bound structure (consistent mechanics that reward learning), separate space and time (the Underworld is virtual with no real-world consequences), and meaning-laden achievement (character relationships deepen, player skill visibly grows). Yet some players report losing themselves entirely—12-hour sessions they didn't intend, prioritizing gameplay over sleep and relationships. When the magic circle ruptures, causal infinity becomes a destructive compulsion rather than liberating exploration.

Minecraft operates through creative infinity: procedurally generated worlds extending infinitely, yet players reshape them according to their vision. The game respects all four pillars—voluntary entry (no failure states), clear rules (crafting systems, survival mechanics), separated space (entirely virtual), and meaning (players define their own achievements). Yet the absence of end-goals and the elegantly looped reward system can generate what behavioral psychologists call "variable ratio reinforcement"—the same mechanism behind slot-machine addiction. When boundaries collapse, the infinite world becomes a trap rather than an invitation.

The pattern is unmistakable: games work when they maintain the magic circle; they become destructive when the circle breaks. A game designer's task is to architect boundaries. The player's task is to remember they can leave.

Play, then Cinema

What Huizinga recognized in historical rituals and games extends to cinema—to narratives that deliberately construct magic circles where character consciousness expands within bounded systems.

Consider Peter Weir's Dead Poets Society. Along with iconic imagery that redefined the way drama is displayed on the big screen, the movie showcases the Welton Academy, which is a rigid magic circle with its own pillars: Tradition(adherence to "the way things are done"), Honor (dignity through duty), Discipline (external control and respect for authority), Excellence (material success, Ivy League admission). These are the rules of Welton's temporary world. Students enter (though compelled, not voluntarily—a critical distinction), accept these constraints, and inhabit the circle's meaning system.

Then John Keating arrives and does something radical: he doesn't destroy the magic circle; he reveals its mutability. He invites students to choose to participate in a new circle—the Dead Poets Society—where the same four pillars are reconstructed. Voluntary entry becomes explicit: boys choose to restart the society. Rule-bound structure emerges through a new set of rituals and codes (the opening verse becomes their binding recitation). Separate space and timemanifests as the cave—a physical location outside Welton's ordinary schedule where different norms apply. Meaning-laden achievement transforms: excellence is no longer about Ivy League admission but about what Keating calls "sucking the marrow out of life."

The boys experience something profound: consciousness expansion within a bounded system. They think more freely, feel more intensely, live with greater intentionality—not because constraints were removed but because they chose new constraints.

Yet the film warns subtly: when the magic circle becomes truly infinite—when boys like Charlie Dalton begin to believe the circle has no boundaries, that rules no longer apply, that the society transcends institutional reality—everything collapses. Charlie's decision to call himself "Nuwanda" and his subsequent actions suggest delusional thinking, a boy who has stepped outside the bounded circle and wandered into genuine infinity without protection. The film's tragedy stems not from the circle itself but from its rupture.

Similarly, Aamir Khan's Taare Zameen Par demonstrates how a properly designed magic circle rescues consciousness from paralysis. Ishaan Awasthi enters the film trapped in a rigid circle—the school system, his family's expectations, the assumption that he is "slow" or "different." He is compelled to participate in this circle; his entry is not voluntary. The boundaries feel like walls, not pathways. Meaning is imposed rather than discovered.

Then Ram Shankar Nikumbh—a visiting art teacher—constructs a new magic circle with different pillars. Voluntary entry becomes central: Ishaan must choose to participate. Rule-bound structure emerges through art as a medium: there are techniques, methods, ways of seeing—but they invite exploration rather than enforce conformity. Separate space and time manifests as the art studio, painting, and the outdoor natural world—spaces where Ishaan's dyslexia becomes irrelevant and his spatial intelligence flourishes. Meaning-laden achievement shifts: success is not academic perfection but the discovery that his difference is not deficit.

Within this new circle, Ishaan's consciousness expands. He moves from shame and paralysis to joy and self-recognition. The film captures what Huizinga understood: that consciousness itself expands within properly designed circles where voluntary participation replaces coercion, where meaning is discovered rather than imposed.

Both films demonstrate a critical insight: the magic circle is not a prison but a prerequisite for consciousness expansion.Children in rigid circles (Welton without Keating, Ishaan's first school) have consciousness constrained, flattened, and distorted. Children in circles where all four pillars are respected (the Dead Poets Society at its best, Nikumbh's art classroom) have consciousness expand. The difference is not the presence or absence of rules but whether those rules are voluntarily entered, genuinely respecting separation from the ordinary world, and generating meaningful achievement.

This reframes how we think about play: it is not escape from reality but the primary mechanism through which human consciousness develops and is nurtured.

The Civic Rulebook

What emerges across chess, Hades II, Minecraft, and the narratives of Keating and Nikumbh is a pattern: bounded systems containing infinite possibility are what enable human flourishing.This insight does not remain confined to games or cinema. It illuminates civilization itself.

Consider the Indian courtroom system, inherited from British colonial law but adapted over centuries. It functions as a perfect instantiation of the magic circle applied to the pursuit of justice. The adversarial system places the court as a neutral arbiter—equivalent to an umpire ensuring fair play. Voluntary entry is codified: you can settle out of court or appeal to higher courts. Rule-bound structure is explicit: rules of evidence, cross-examination procedures, standards of burden of proof. These are not natural laws but agreed-upon constraints transforming the infinity of "all possible arguments and interpretations" into navigable legal proceedings. Separate space and time manifests concretely: within courtroom walls, violence is replaced by rhetoric; outside, disputes might be resolved through coercion. Meaning-laden achievement emerges as verdict: a singular decision transforming infinite ambiguity into definitive judgment. The magic circle works because all parties accept its boundaries.

Modern diplomacy operates identically. Nations negotiate within frameworks—the United Nations, trade agreements, customary international law—functioning as mutually agreed rules. Game theory, central to diplomatic analysis, recognizes this explicitly: international relations are games where actors model payoffs and identify strategies that shift outcomes toward their interests without triggering mutual destruction. Trade agreements prune infinite possibility into finite, navigable clauses. Both parties voluntarily sign; both operate within rules defining tariffs, dispute resolution, renegotiation triggers. Trade occurs within separated space and time—distinct from military conflict or forced extraction. The agreement carries meaning: it signals trust, opens markets, creates incentives for continued cooperation.

Yet when the magic circle ruptures at civilizational scale, the consequences mirror Morphy's madness or the destruction of Welton's community. The resource curse—observed in Nigeria, Venezuela, the Democratic Republic of Congo—provides the archetype. When a nation discovers abundant resources, governance boundaries collapse: officials no longer need to tax citizens or remain accountable; they extract resources directly. Voluntary participation dissolves. Rules lose meaning. The bounded infinity that might have fostered cooperative nation-building transforms into zero-sum competition.

This competition attracts external actors. If I fund one faction, I gain resource access – and this further pushes the phenomenon of local rebel groups willing to accept foreign support. Civil war ignites—sustained by proxy financing from external powers seeking economic or geopolitical advantage. Syria, Yemen, Congo: in each, resource abundance transmuted into conflict. The infinite possibility space—all ways a resource-rich nation could develop—collapsed into a single bloody equilibrium.

The parallel is exact: Morphy lost himself when the magic circle of chess collapsed, exchanging structured play for obsessive compulsion; nations collapse into civil war when governance boundaries rupture, exchanging cooperative rule-following for destructive competition. In both cases, the infinite becomes catastrophic once the protection of the magic circle—the agreed-upon separation of engagement types—is removed.

This suggests that civilization is fundamentally a game design problem. We design institutions (courtrooms, trade agreements, diplomatic protocols, democratic processes) that enable voluntary participation, establish clear rules, create separate spaces where special norms apply, and generate meaning-laden outcomes. When these four pillars are maintained, societies cooperate, innovate, and prosper. When they collapse—when rules lose meaning, when exits become impossible, when separation between elite and commons erodes—civilization transforms into tyranny or chaos.

Game designers, in crafting bounded spaces containing infinite possibility, practice the same fundamental art that built legal systems, international order, and democratic governance.

They are architects of human flourishing, whether they know it or not.

The exit door

We are the animals who want to know infinity. Chess contains 1,012,010,120 possible games; we will never exhaust its depths. Hades II generates unique configurations across hundreds of runs; we will never map all of its possibility. Minecraft extends endlessly in every direction; we will never fully explore. And civilization itself—the legal systems, trade networks, diplomatic protocols binding billions of strangers—is a bounded infinite game we all play together.

But the trajectory from Morphy's madness to civilization's structures reveals a truth Huizinga understood: infinity is beautiful within bounds but catastrophic without them. The magic circle is not a limitation on human freedom; it is the mechanism through which freedom becomes possible. Huizinga's four pillars—voluntary engagement, rule-bound structure, separated space and time, meaning-laden achievement—are not restrictions imposed upon us.

They are the conditions allowing infinite possibility to exist without overwhelming us.

Yet there remains something worth considering—something that haunts the edges of this framework. What if, as a conscious agent, one simply decided to reject the magic circles that contain them? What if they woke up tomorrow and chose to stop following the rules of courtrooms, markets, institutions, and professional identities? What if they decided that the consensus reality governing billions is simply one possible game among infinite alternatives—and they would rather play by your own rules?

Legally, ethically, practically, the world has mechanisms to prevent such defection. But Huizinga insists that play is fundamentally voluntary—that authentic play cannot be coerced. If civilization is a game, then its ultimate vulnerability is that participation must remain chosen. Every courtroom verdict, every trade agreement, every democratic election, every law we follow—these work only because we collectively choose their boundaries, collectively agree this circle contains something worth protecting.

Science itself exemplifies this. Scientific knowledge is not an absolute truth but a set of agreed-upon methods and interpretations—a magic circle where certain evidence counts, where peer review maintains boundaries, where replication governs validity. Different interpretations compete not because one is "more true" but because the community agrees it fits better within established rules. Even our understanding of reality is an interpretation, a game we play with nature, bounded by methods we accept.

What would it mean to step outside this circle? To recognize that all of them—civilization, science, commerce, law, language itself—are games we play, bounded spaces we inhabit because they are meaningful, not because they are inevitable? There is freedom in this recognition. But there is also vertigo. For if all games are choices, then refusing one circle means entering another, constructing new boundaries to replace the ones you rejected. The infinite cannot be inhabited; it can only be navigated through bounded encounters.

Perhaps the deepest revelation is this: we are beings capable of conceiving infinity, yet we can only live within boundaries. We are creatures who want to know unboundedness but can only survive by building circles to contain it. Every game, from ancient chess to digital worlds to civilization itself, is a testimony to this paradox. We make these circles not because infinity is dangerous—though sometimes it is—but because creating meaning requires constraints. Freedom requires structure. Possibility requires boundaries.

The question is not whether to play, for we are already playing, embedded in games we did not consciously choose. The question is whether we will play consciously, maintaining Huizinga's four pillars deliberately, or whether we will let the magic circles collapse, allowing infinity to overwhelm us. And perhaps most unsettling: recognizing that the choice to play or not to play is itself an illusion, for refusing to play is simply playing by a different set of rules you have not yet fully recognized.

In the end, we microdose infinity not because we are weak, but because we are wise enough to know that some powers are best approached in careful, bounded encounters.

In play, we become human. In bounded play, we become civilized.

And in recognizing that civilization itself is play, we become something stranger still: conscious participants in games we will never fully understand, freely choosing boundaries that may have always been our only path to meaning.